Meet the Shingle Dig Team! A dedicated group of volunteers unearthing the story of the Shingle House, one sift at a time…

-

George Knight

-

Dot Zwerin & Peg Ross in the Archaeological Dig Lab

-

Mike Mohyla & Mike Tulin

“Team Shingle House”-2022”

By Kim Evans & Sam Calabrese

Warwick Historical Society

The Warwick Historical Society’s “Shingle House” is located at 9 Forester Avenue and it is the oldest house in the Village of Warwick. It is the first property that was acquired by the Historical Society in 1915 and it serves as the flagship home in the group of twelve structures currently available for touring to the public.

Members of “Team Shingle House” sat down with Kim Evans and Sam Calabrese for a conversation about how they came together to work at the Shingle House dig. George Knight, Mike Mohyla, Peg Ross, Mike Tulin, and Dot Zwerin shared their thoughts on the archeological project and the discoveries they have found.

How did you get involved in the project?

Dot Zwerin, age 88, was volunteering in the clothing department at the Historical Society when George brought in a button he found at the dig to see if they could determine the age. He asked her if she might like to join the team. “I was so excited because when I was a young woman, all I could be was a nurse, a teacher or a secretary,” she said. “He challenged me to help out and I was determined not to fail.

George Knight,78, said Dot used to throw three 200-pound buckets into the sifter. “Nobody messed with her! The project started out in 2013 as a day of metal detecting by a local history club. Michael Bertolini, curator and then president of the Historical Society, supervised the eight and nine year olds. Prior to the initial discoveries by the Club, the only thing visible was green grass on a large lawn.”

“The kids found glass shards right away,” George said. “One parent was a commercial archeologist and he volunteered to set up a grid and laid out a map of the future pit. The first find was the top brick of a cistern that Michael recognized and identified. Everything we discover was owned by the people who lived in the house. Unlike Mt. Vernon, where items are from the period, but are brought in to replicate what it could have looked like.”

Peg Ross, 74, explained the work she and Dot do each day. “We clean the artifacts that the guys bring us.The items are in buckets covered in dirt and rock. We clean them with water, separate everything, document how many pieces, the type of material; glass, nails and white crockery.Then we categorize and mark them according to the area and depth of the pit where they were discovered. We could put everything back if we wanted to, because we know exactly where they were found. One recent find is the heel of a shoe, which is so wonderful. You can’t help wondering who wore it and what their life was like.”

“I enjoy knowing we are the first ones to discover an artifact,” said recently retired team member, Mike Tulin. “Doing it for ten years, we have all learned a lot. I value the friendships we’ve developed and we enjoy being together. I look forward to it every day.”

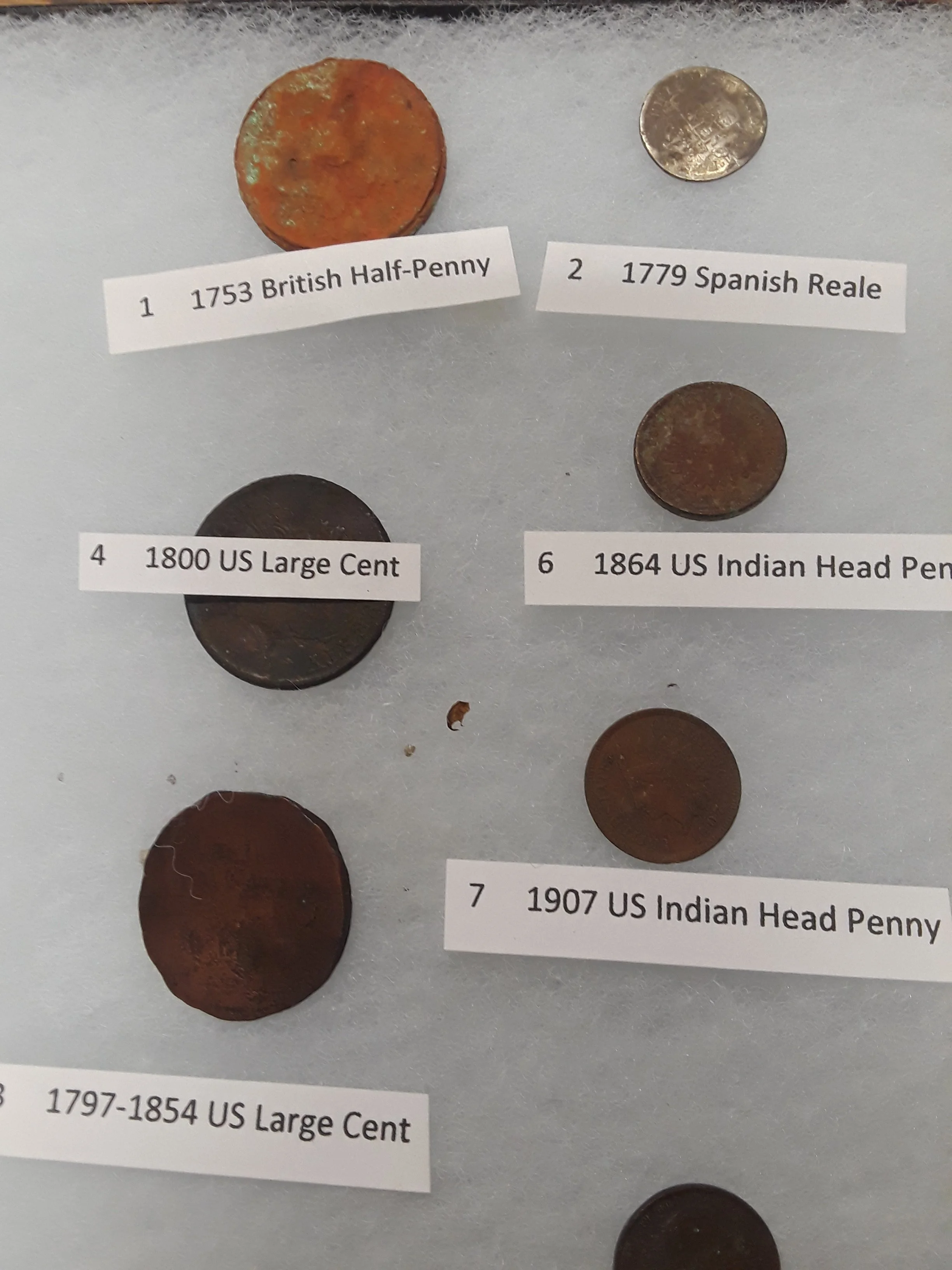

Mike Mohyla, 68, and also retired, laughed and said, “My wife suggested I couldn’t be in our house anymore. I noticed an article in the Advertiser about the dig, so I met George and he invited me to join the group. I always wanted to be an archeologist as a kid, so I can’t wait to get out in the pit. We recently found a rectangular block buried in the dirt that I can’t wait to get in there to see what it might be. I love the coins we find because of the dating. The oldest is a Spanish piece from the 1770s and a British half-penny from 1753. It’s fun to consider that the people who had that coin also had a King. That’s why we flew both the colonial flag and the Union Jack at a recent open house.”

Can you tell us a little about the people who built the house?

“The people who lived here were thrifty, frugal Yankee farmers,” said George. “We researched the progression of owners and it took a long time to determine that the house was built in two pieces. Artifacts have to be fit into the timeline and sometimes we have to change our chronology, based on new artifacts we find. George explained that the house was built in 1764 for Daniel Burt Jr. and his wife, Martha. Built as a defense against Native American attacks, she was from Connecticut and had bad things happen to her family from the tribes in the area. So she did a “colonial prenup of sorts” with her husband, indicating she wouldn’t join him in Warwick unless the home was made of stone.

George continues, “We found the stone house by accident, and we didn’t realize what we had actually found because of the original grade. The 1764 house is what we are currently excavating. The cistern that collected rain water was buried intact under eight inches under the grade. It was watertight and collected water from the roof. We also found a stone lined privy called ‘a necessary.’At the time, ‘night soil collectors’ would come and empty out the privies and process the contents with simple chemicals extracting potassium nitrate crystals to produce black gun powder. A lot of glass shards are found in the privies to keep children and livestock safe, because they didn’t wear shoes.”

It looks like painstaking work. Do your team members have expertise in archeological projects?

“We are volunteers who have a genuine interest in archeology. We consider ourselves ‘History Detectives,’said George. “We are not archeologists, but we use their techniques, tools and methods to do what we do. None of us have specific degrees…except for the school of experience and mastering the techniques isn’t hard. We’re a group of older folks who are motivated by the challenge of finding something unique that was around 200 years ago; things that haven’t seen daylight in that span of time. We’re the first one to discover them. So, in the past ten years, we’ve learned a lot. I’d like to recognize the additional team members who are significant contributors to any success we have had: Vicki Braidotti, Arnold Vila, Ivy Tulin and Alina Badia de Lacour.”

“What are some of the items you find the most interesting?”

“Bottles were found in the privy and ash pit,” said Dot. “Medicine bottles and liquor flasks with a seven ounce mark. It helped the bar keep at the tavern know how far to fill the bottle with keg whiskey. Opium bottles are the small ones…ladies kept them in their dresses as ‘Mother’s little helper.’ A sad story is the murder bottle; a flat bottle with a rubber hose that babies and toddlers drank their milk or water from. Eight of ten children died from bacteria in the bottles. Cocaine and heroin use offset the addiction to opium. Dr. Hall, local county historian, says Warwick was high as a kite during the time.” Dot continues, “The blue plate was found in four pieces in the privy. Lafayette came to visit in 1824 and the state of New York gave him a parade and the plate was given to him. Many artifacts were intact in the privy.”

“Tell us more about how you validate your findings.”

“Although we are amateurs,” George says, “Michael Bertolini’s expertise provides immediate reference to quantify items. He has a tremendous background as a curator and mentions he wished he had been an archeologist. We rely on him often and I can proudly say no one knows more than we do in dirty detail. None of us expected to be here ten years…but it keeps leading us on. Perhaps we’ll try to do two more seasons. It’s very addictive and we can hardly wait to come back when we have to close for the winter.”

“If you had a wish list of equipment that might help you in your work, what would it be?”

“We’d like to make this space an educational area. Plexiglass to cover the items for display would be great,” said Dot. Both Mikes said, “A spectrograph to determine the composition of the items, a scaler, mini jack hammer, a small x ray system and a GPR machine, which is like a dental x ray machine. Maybe even a bobcat and a backhoe, if we’re dreaming! All funding for the project is provided by the Historical Society, so if a benefactor is interested in helping, we’d love it.”

“If people are interested in volunteering at the Dig or want to help out with a monetary contribution, who do they contact?”

“We welcome anyone who is interested in helping,” said George. “Feel free to contact the executive director Nora Gurvich at the Historical Society at 845-986-3236 email at Nora at director@whsny.org.

Thank you for the opportunity to tell our story.”